“The age of post-truth stretches as far back as you care to look, there never has been a golden age of transparency”, said Steven Poole in one of its most recent pieces in The Guardian, illustrating the vast history behind the infamous expression (1). Fake news is nowadays hijacked and repurposed term but its semantics are widespread in both space and time.

The first well-documented narrative mentioning published non-factual information dates back to 36 BC when Octavian, adoptive son of Julius Caesar, launched a campaign to downplay Marcus Antonius, Roman politician and general, claiming he didn’t respect traditional Roman values like faithfulness and respect. This constituted leverage for Octavian to win the civil war and achieve the support of the people contributing to his proclamation as the first Roman emperor (2).

Several centuries have passed until a theorization around the topic started to take place. During the 16th century, the first references to “false news” were identified (1). Before the term fake was recognized as an adjective in the 18th century, Francis Bacon described the phenomenon we coin now as confirmation bias in Novum Organum (1620) and Thomas Browne, in Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646), exposed the ubiquitously noxious nature of these made-up pieces of information (3) (4). Other terms arose throughout the 17th century to illustrate this reality, such as “fictitious” (1624) and “ultra-crepitant” (1640), but it was not until the 18th century that the phenomenon started to become heavily considered due to its increasingly growing dimension (1).

The Catholic Church’s false exploration of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake claiming “that the earthquake was a punishment by God for the sins of the world” prompted Voltaire to speak out against religious dominance constituting one of the starting points for the establishment of the free press in the scope of the Enlightenment intellectual movement (5). The Marquis of Condorcet, a French philosopher and mathematician, expanded on this event stating that a press free from censorship would circulate an open exchange of ideas, with logic and truth winning out but this idea was not warmly embraced everywhere (6). John Addams, the second president of the United States of America, worried about the fact that success and legitimacy were dependent on public opinion, reacted to Condorcet’s progressive statement by saying that “there has been more new error propagated by the press in the last ten years than in a hundred years before 1798” (6). Adams’ marginal response reminds us that when something as important as truth is up for discussion, it opens the possibility for evil actors to spread lies — what today’s readers may term as fake news. John Adams’ dissatisfaction was previously shared by figures such as Thomas Hutchinson, a British loyalist politician, who lamented that press freedom had been interpreted as the freedom to “print everything that is libellous and slanderous”. In 1765, arsonists burned Hutchinson’s house to the ground over the Stamp Act, despite the loyalist’s opposition to the despised tax, a perfect parallel to the recent pizzagate conspiracy, which culminated in the shooting of a Washington, D.C. pizza parlour sparked by false news stories (6).

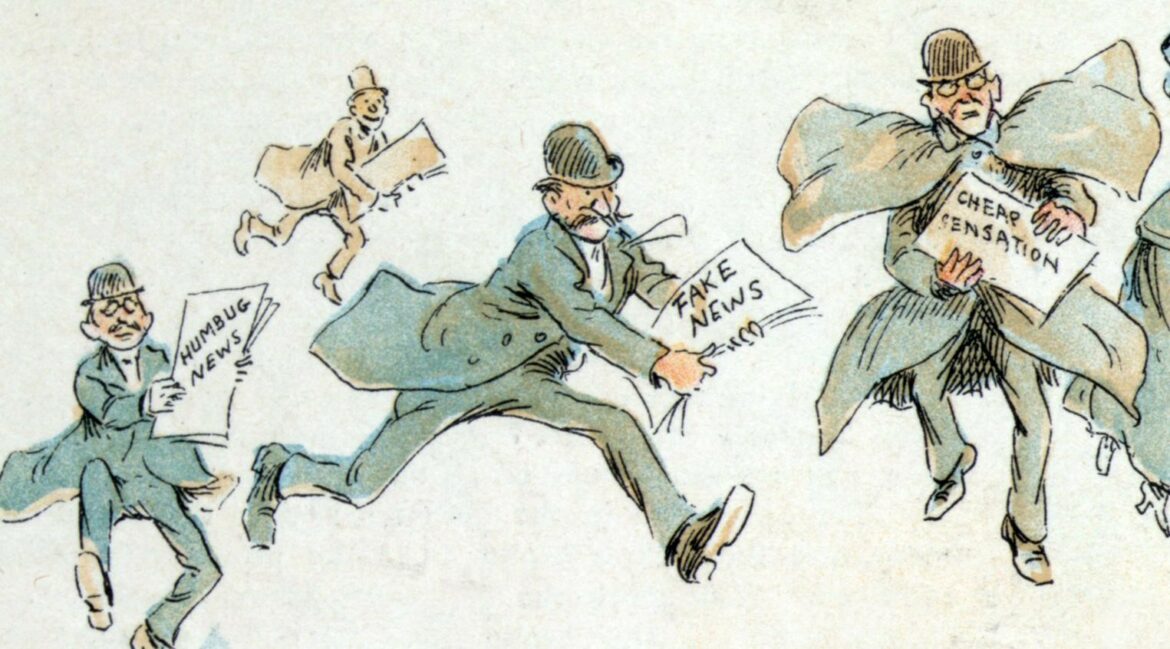

The 19th century was notorious for the rise of popularity of modern newspapers (7). Unfortunately, alongside this acclaim, fake stories also started to acquire a “pandemic” status. The first considerable occurrence happened in 1835 when The New York Sun published a piece named “The Great Moon Hoax” describing how a well-known astronomer discovered fantastic animals of alien nature on the moon. This article was one of the main contributors to the leading role of the newspaper at that time (2). Later that century, the rivalry between Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, proprietors of sensationalist newspapers, gave rise to the concept of yellow journalism, which was marked by exaggeration and alarming headlines aimed at gaining attention and, most importantly, revenue (7). In fact, William Hearst’s sensationalistic coverage of the Spanish-American War in 1898 helped rocket him to national stardom. Aside from horrible pieces portraying Cuba’s socio-political state, Hearst’s correspondents unambiguously accused the Spanish of the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor, prompting popular outrage in the United States that was ultimately translated into a demand for intervention and, consequently, war. This was considered by many the first press-driven war (7). It was also during this period that the use of the term fake news was documented for the first time (5).

Nevertheless, the late 19th century’s sensationalist rush was actually a driver for change in the contemporary information paradigm. At the turn of the 20th century and motivated by the vicissitudes of war, people started to look for more objective news sparking the rise of relatively objective journalism as an industry (7). One of the major contributors to this silver age (as said before, there was never a golden age!) of journalism was The New York Times which based its approach on facts about business and general daily information. This business model built around objectivity became, until recently, the dominant one (7). Of course, objective journalism had its flaws, most notably during World War II with Nazi propaganda aimed at inflating anti-Semitism, but it wasn’t until the birth of web-generated news that this paradigm started to become significantly challenged, and fake news resurfaced as a major force (5) (7). The digital aspect was ultimately responsible for digging yellow journalism from its grave, reviving it in some kind of mutant form characterized by being more resilient and ubiquitous, perfectly aligned with what people perceive nowadays as fake news. Algorithms creating news feeds are becoming more and more infamous concerning accuracy and objectivity, the digital trend keeps crashing the conventional, objectively-oriented, independent press’s financial and human resources, and I could be perpetually listing other related aspects but the important thing here is recognizing that the current circumstances are jeopardizing the truthfulness of the information in which we rely on and that constitutes a societal issue (7).

In a world where people are sceptical about reliable news sources and, at the same time, open to digest media- and government-biased information, real news is most likely to dwindle, giving fake news a space to grow. We’ve seen in this article the dreadful consequences of this along with history so finding a new way to stop the rising flood should become one of our ultimate objectives.

Rafael Luis Pereira Santos

References

(1) Pool S. (2019), “Before Trump: the real history of fake news”, The Guardian.

(2) Bitesize, “A brief history of fake news”, BBC.

(3) Bacon F. (1620), “Novum Organum”, The Works, 3 vols., 3: 343-71.

(4) Browne T. (1646), “Pseudodoxia epidemica, or, Enquiries into very many received tenents and commonly presumed truths”, T.H. for E. Dod, London.

(5) CiTS, “A Brief Story of Fake News”.

(6) Mansky J. (2018), “The Age-Old Problem of Fake News”, Smithsonian Magazine.

(7) Soll J. (2016), “The Long and Brutal History of Fake News”, PoliticoMagazine.