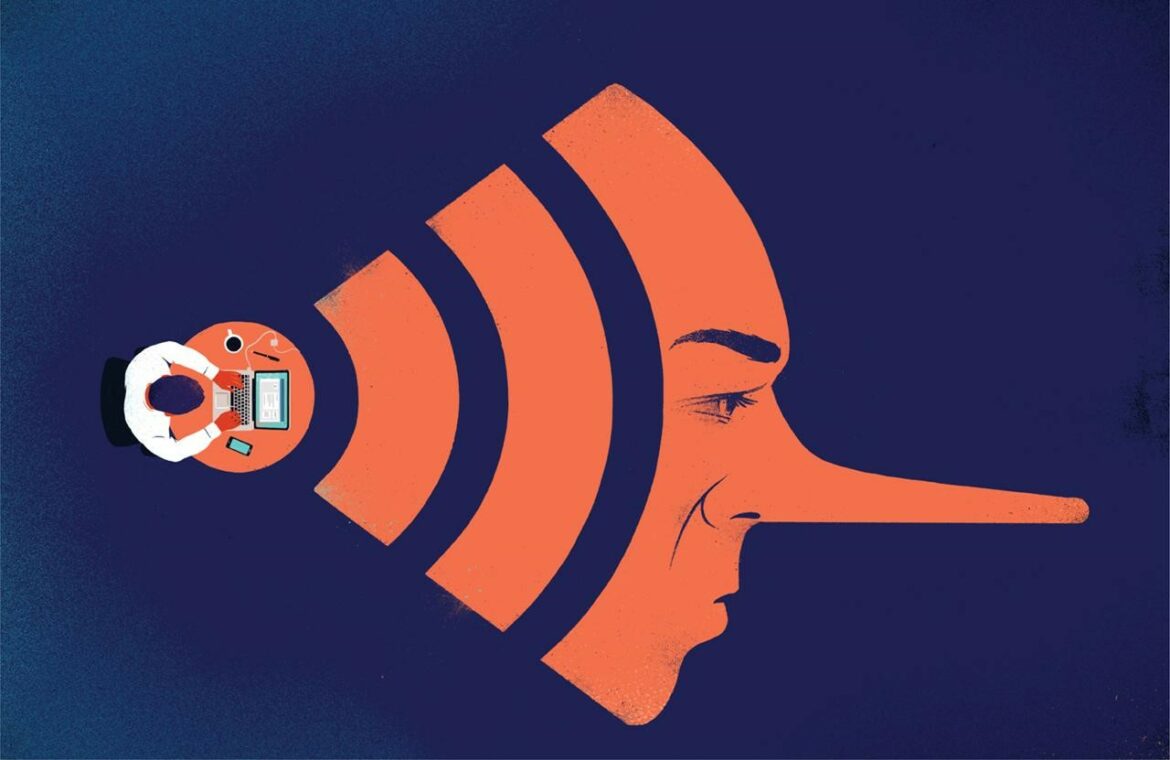

Fake news became a widespread term, especially after the blossoming of the internet and social media as privileged platforms to communicate, interact and acquire information. In order to give a clear understanding of fake news, I will start by reviewing some definitions taken from different online dictionaries. Cambridge dictionary defines fake news as: “false stories that appear to be news, spread on the internet or using other media, usually created to influence political views or as a joke”.

Dictionary.com defines fake news as false news stories, often of a sensational nature, created to be widely shared or distributed for the purpose of generating revenue, or promoting or discrediting a public figure, political movement, company, etc. And as a parody that presents current events or other news topics for humorous effect in an obviously satirical imitation of journalism.

From these two definitions, we can identify some common characteristics. Specifically, fake news is: false, misleading, able to change the audience’s opinion. This last element reminds us of the relational nature of fake news. In fact, it is important to mention that fake news do not exist without circulation. And circulation is the exact mechanism that makes them so dangerous, especially in the internet era. Parallelism could be made with art. Imagine a painter that creates the most amazing artwork. Unfortunately, this painting remains invisible in his studio, which no one ever visits. Therefore, the only audience the artwork has is the creator itself. Consequently, no one will benefit from the painter’s skills or the painting’s beauty, no one will appreciate his art and he will not make any connection with fellow colleagues or gallerists. Someone could say that this hidden painting is not even an artwork, as it is not exposed to external scrutiny. The same mechanism works for fake news: if they do not circulate, users will not have knowledge of their content. Therefore, opinions will not be shaped around misinformative content.

But what does misinformation mean?

The term is frequently used as a synonym of disinformation, although its meaning is different and strictly related to a matter of intentionality. In fact, misinformation generally applies in a context where the user has no intention to harm or spread wrong information. We could say the user genuinely believes the news is worth spreading because of its truth. On the contrary, disinformation is connected to an intentional action: this is the most dangerous practice as it is specifically designed to trick the user into a cycle of fake news. Ultimately, the effect of misinformation and disinformation is the same: they both lead to creating a fake news cycle.

In the internet era, algorithms play a huge part. Algorithms are instructions. The internet works on them and internet search is accomplished through them. Also, algorithms are fed by our online behaviour. In order to clarify, let’s make a connection with online shopping. When we buy a pair of shoes online, or just search for different options, we create a “taste path” around shoes. This makes the online algorithm present to us similar options every time we search for the same item, based on our preferences. In addition, as some social media works on commercials, we will most likely see shoe advertisements shown in our feed, even if we do not intentionally search for them. This is a marketing strategy, which creates “false” desires based on the continuous visualisation of pleasant images – for instance, the pair of shoes we like and most want – leading the user to cognitively resettle their necessities.

Similarly, when we encounter fake news, read them and share them, we create a path based on our tastes and beliefs. The algorithm works on a “continuous learning” basis: the more we interact with online content – whether it is shopping or fake news – the better the algorithm becomes in knowing what suits us best. We said before that fake news is false and misleading and needs to circulate in order to spread.

So, why do we spread fake news? Here come two other components: fact-checking and the susceptibility of users. Fact-checking is connected to the research. Despite being a good practice, it can be subject to human flaws such as subjectivity and experience confirmation, as well as being very time-consuming. Therefore, when we get in contact with the news, we tend to take for granted their truthfulness. This is even more relevant when the news is read on the internet. Elements such as the rapid speed of social media regarding content creation and dissemination, as well as sensationalist headlines, leave the user with the assumption that what they are reading is true. Therefore, it is their duty to share and let others know the truth.

To help fact-checking grow as a practice, websites such as Snopes and Politifact have been created, in order for the user to verify information in the news cycle and avoid human-checking failings. A problem related to fake news is also the susceptibility of users, which is the internal characteristics related to the person who reads and decides to share fake news without undertaking a process of verification. As a general rule, we do prefer information that comes from trusted – but not necessarily informed – sources. This means that we are cognitively prone to believe content coming from our friends or inner circle. And friends are also the group we connect on Facebook with. The psychological process is very simple: I trust my friend, therefore I do not need to verify.

Moreover, we are prone to read and share information about risk. This is why fake news circulation is particularly high before and during political election campaigns, crises, natural disasters or any major social or political event. This is an inner psychological mechanism, which perfectly marries the practice of public opinion’s control. Most social media managers working on political campaigns design accurate strategies, in order to build an online reading-sharing mechanism of fake news with the aim of discrediting the opponent’s public and personal life.

Ultimately, these cognitive biases are entangled with our evolutionary past. Once a behaviour is set and proven to be working, we internalize it in order to minimize risks. The more we associate with the behaviour, the stronger it becomes. When we are kids, we have no knowledge of the danger of crossing a street when a car is passing by. Our parents hold our hands when crossing, they are emotionally alert and show us the right way to proceed. After a time, we internalize this behaviour as safe: we autonomously wait for the green light, cross on the pedestrian crossing and are aware of the speed of the car and the distance between it and our bodies. This minimizes the risk of being hurt.

But how can we protect ourselves from fake news and stop the circulation cycle, in our online environment at least? Many researchers are now working on the use of machine algorithms to facilitate the detection of false information. Websites such as the already-mentioned Snopes and Politifact are options that help us double-check sources and facts. Ultimately, being aware of the incredible amount of fake news circulating should enable us to be less simplistic regarding the accuracy of what we read online.

Carlotta Sofia Grassi