The problem of the burka is not a religious problem, it’s a problem of liberty and women’s dignity. It’s not a religious symbol, but a sign of subservience and debasement. I want to say solemnly, the burka is not welcome in France. In our country, we can’t accept women prisoners behind a screen, cut off from all social life, deprived of all identity. That’s not our idea of freedom. (Former French president Nicolas Sarcozy in his first state of the nation speech) In a world plagued by humanitarian crises, environmental turmoil and political polarization, women’s clothing may appear to be a matter of little importance. It would perhaps seem better suited for a fashion blog or a lifestyle magazine. Nevertheless, as the above quotes suggest, the question of how women should dress is surrounded by deeply entrenched, strongly conflicting narratives. In our multicultural societies, the clothes women wear – or do not wear – have become significant points of contention. This is not only visible in the views on covering up expressed by Islamic and French authorities respectively.

The clashing narratives also very much affect the concrete, lived lives of women around the world. Every day, millions of women are confronted with strong opinions about the way they dress. Every day, women are forced to ask themselves: how does what I wear affect the people around me? What perceptions and preconceptions will society have of me, based on my clothes? Will I be viewed, judged or treated a certain way? In some cases, the question of clothing even becomes a question of human security: can the way I dress put me in danger? If someone assaults me, will society silently accept it as a natural consequence of my attire?

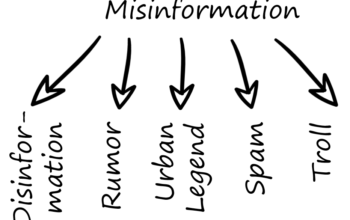

How did the question of women’s clothing become such a potent social and political issue – particularly the question of the Islamic veil? Some researchers trace this development back to the 9/11 attacks in America. Prior to these events, Western societies, in general, did not pay much attention to Muslims. The Arab minority in the USA even expressed a feeling of being ‘invisible’ to the majority of Americans. 9/11. However, brought about an enormous shift. Suddenly, Muslims were the central theme of news media, security policies, and public debate. Islam was no longer ‘just’ a religion, it was portrayed as a fundamental danger to Western society. Its followers became the most scrutinized group of people in the world. The ultimate visual representation of this group were women wearing various forms of veils. The veil came to symbolize not religious and cultural diversity, but a perceived security threat. It became closely associated with violent extremism. By covering up her body, then, the Muslim woman suddenly started to arouse suspicion. This suspicion manifests itself in potentially terrifying ways: Many headscarved women have found themselves, victims of attacks, while driving their cars or walking in public. The image of the headscarf triggers a violent reaction from strangers who scream out racial and religious epithets such as violent extremism, a “f*ing Muslim,” along with demands that they “go home” and get out of America. Many Muslim women have their headscarves ripped off by their assailants (Aziz, 2012).

How did the question of women’s clothing become such a potent social and political issue – particularly the question of the Islamic veil? Some researchers trace this development back to the 9/11 attacks in America. Prior to these events, Western societies, in general, did not pay much attention to Muslims. The Arab minority in the USA even expressed a feeling of being ‘invisible’ to the majority of Americans. 9/11. However, brought about an enormous shift. Suddenly, Muslims were the central theme of news media, security policies, and public debate. Islam was no longer ‘just’ a religion, it was portrayed as a fundamental danger to Western society. Its followers became the most scrutinized group of people in the world. The ultimate visual representation of this group were women wearing various forms of veils. The veil came to symbolize not religious and cultural diversity, but a perceived security threat. It became closely associated with violent extremism. By covering up her body, then, the Muslim woman suddenly started to arouse suspicion. This suspicion manifests itself in potentially terrifying ways: Many headscarved women have found themselves, victims of attacks, while driving their cars or walking in public. The image of the headscarf triggers a violent reaction from strangers who scream out racial and religious epithets such as violent extremism, a “f*ing Muslim,” along with demands that they “go home” and get out of America. Many Muslim women have their headscarves ripped off by their assailants (Aziz, 2012).

These violent reactions are not isolated events. On the contrary, reports indicate a robust pattern: the majority of hate crimes against Muslims are directed at women wearing veils. These women, then, are not only targets of social scrutiny and suspicion – they are at real risk of physical violence. This narrative of threat, however, is not the only one surrounding Muslim women’s clothing. Another dominant view is the stereotype of the victim. This stereotype is particularly visible in the initial quote from French leader Sarkozy: by covering up, the Muslim woman is ‘imprisoned’. She is subservient and debased, deprived of freedom. The idea that a woman can choose to cover up, by her own free will, is incompatible with this stereotype.

So – what happens when the roles are reversed? What is it like to be a non-Muslim in a predominantly Muslim society, following western dress codes? When the social norm for women is to, as the Qur’an says, “draw their cloaks close round them”, how do people react to those women who don’t cover-up? First and foremost, women are strongly urged to avoid challenging this norm at all. Much of the traveling advice for western women visiting the Arab world focuses on exactly the aspect of covering up. Lonely Planet writes: How women travelers dress goes a long way towards determining how they’re treated. To you, short pants and a tight top might be an appropriate reaction to the desert temperatures, but to many local men, your dress choice will send an entirely different message, confirming the worst views held of Western women.

Unlike the issue of Muslim women in the West, very little research is available on the perceptions of Western women in the Muslim world. What those ‘views’ alluded to in the quote above entails, then, can only be backed up by anecdotal evidence: Arab views of the contemporary western woman are also highly sexualized. In fact, many Arab men, particularly those with little contact with the west, have this fantasy of western women that comes straight out of Playboy magazine or the grainy images of pirate pornos. In this view, western women are oversexed, promiscuous and have revolving doors in their knickers (Diab, 2010) Whether or not there really exists an Arab narrative of “the Western Aphrodite”, there is no doubt that sexual harassment of non-native women is widespread. A study by the Egyptian Centre for Women’s Rights found that 98% of female foreigners surveyed had been sexually harassed. The harassment comes in various forms: inappropriate staring, comments, stalking and groping, even sexual assault.

Whether you are covered up or not, then, the clothes you wear as a woman will affect the way different societies perceive and treat you. All over the world, women are caught in the middle of the clashing narratives surrounding the way they dress. However, as the pictures running through this article show, women are fighting to create their own narratives: you can wear a hijab while still being free and independent. You can show your body while still maintaining your dignity and self-respect. These are the alternative narratives of women’s clothing.

Johanne Kalsaas

Sources:

Aziz (2012). Oxford Islamic Studies. Terrorism and the Muslim “veil”. Available here: http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/Public/focus/essay1009_terrorism_and_the_muslim_veil.html

Diab (2010). The Guardian. The Arab myth of Western women. Available here: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/nov/10/arab-myth-of-western-women

Lonely Planet. Middle East: Women travellers. Available here: https://www.lonelyplanet.com/middle-east/women-travellers Rogers (2011).

CNN. Egypt’s harassed women need their own revolution. Available here: http://edition.cnn.com/2011/OPINION/02/16/rogers.egypt.sexual.harrassment/index.html

Soltani (2016). Confronting prejudice against Muslim women. Available here: https://unu.edu/publications/articles/confronting-prejudice-against-muslim-women-in-the-west.html