Photography is considered the art of portraying reality. A shot can define a portion of space, capture movements and people and at the same time contain emotions, expectations, intentions. But what reality are we talking about? Indeed, if it is true that photography is a form of art, we must start from the assumption that the artist’s vision is unique and particular. The idea lies precisely in deciding which subject to portray, and which message to associate to the image. This is the case of the picture taken by photographer Laurence Brun.

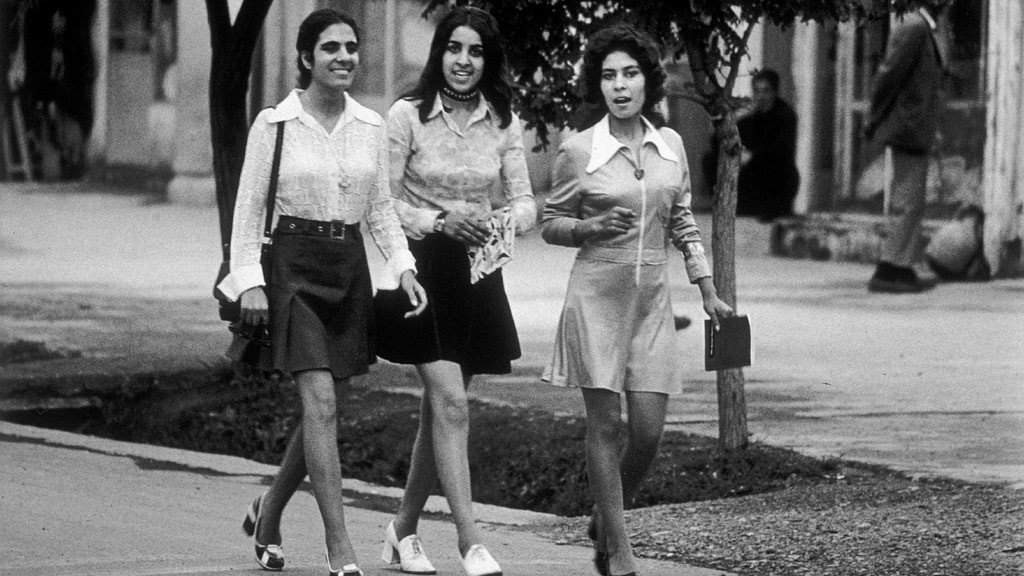

It is 1972, we are in Kabul, Afghanistan, in the Shahr-e Naw neighborhood. The image portrays three smiling young women. Dressed in a miniskirt with hair blowing in the wind. From the image it can be deduced that customs have changed, that the freedom of expression of women was much greater than today. The iconic photograph was the subject of media interest a few years ago, recently returning to the fore with the fall of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan at the hands of the Taliban last August 2021. Laurence Brun, in an interview with Le Monde, declares: “Since 2001, this photo got out of hand, and everyone started talking about it and fantasizing about it. This has deeply irritated me”.

The irritation stems from the fact that, fifty years later, this photograph was used as a political tool, to emphasize that Afghan women in the 1960s and 1970s had truly emancipated themselves and experienced a period of freedom of fashion and costumes, before the state fell back into obscurantism. At least this is the common narrative. Laurence Brun goes on to say that the decision to take that photograph regarded the exceptional nature of the image itself that was appearing in front of her eyes. It was a rare occurrence to meet women dressed like that in Kabul: clothing that let the shapes shine through was therefore definitely not the norm.

The photographer, aware of the isolated perspective which could easily lead to misinterpretation, decides to take other photographs in which women dressed differently to one another appear. In particular, doing justice to the complexity of customs and traditions, placing women with hijab and miniskirt side by side in the same urban space.

Source: Laurence Brun

Historical Background

It is important to give a historical picture of Afghanistan at the time the photograph was taken, to avoid making the same uninformed mistake that unleashed a domino of events. Afghanistan actually went through a period of major reforms in the 1960s. In fact, the country was ruled by King Mohammad Zaher Shah. The king questioned the use of chadri as an imposition, considering it a reason for the isolation of Afghan women from social life. In 1959, Afghan women had the possibility to decide whether to wear the chadri or not, many continued to cover themselves, especially in rural areas.

In parallel and thanks to other reforms, other women had access to university studies and started working in factories or offices, especially in the capital Kabul. From these considerations, it is evident the powerful distinction between women living in the countryside and women living in the capital Kabul, where the photograph was taken. Under Shah’s rule, Afghanistan became a parliamentary monarchy. Entertainment venues, such as cafes, cinemas and concert venues, started to flourish in the capital. Again these changes, which take hold in the capital, do not take root elsewhere. Since 1969, a great drought hits Afghanistan. While the king is engaged in economic modernization and reforms related to women’s rights in the capital, the gap between the countryside and the city becomes more evident as many peasants begin to starve.

These facts led to a military coup: the army takes power in Kabul and the king is sent into exile. His place is taken by his cousin, Mohammad Daoud Khan, with the support of soldiers from the Soviet Union. A rapid succession of governments followed, emblematic of the political instability of Afghanistan. The latest reforms, made by Hafizullah Amin, make education compulsory for young women, but prohibit prayer in mosques and hijab in public spaces. Both issues are a matter of honor for more conservative families and civil society does not react well to the news.

Ultimately, there have been reforms, but their fragility, inserted in a complex socio-economic context such as that of Afghanistan in the 1960s and 1970s, did not allow their results to be effective and long lasting. For this reason, it is reckless and dangerous to talk about a past “liberation”, especially if this narrative justifies the will to help Afghanistan return to a nostalgic and radiant past. It is probably wiser to ask ourselves if this past ever existed.

What did this photograph unleashed? Despite Brun’s good intentions, the circulation of the picture led to a widespread exploitation of its content, especially on social media and by far-right groups in Europe and the United States. Moreover, to make the decontextualized content of the photograph more captivating, the picture of the three women is often found on social networks combined with other photographs that show women in burqas or hijabs. On the other hand, no mention is made of other pictures taken by Brun in Afghanistan during the same period, which portray a different and multifaceted Afghanistan. The force unleashed by this image is enough to fuel an uninformed debate about the Afghanistan situation of the times compared to that of today. Ultimately, justifying decisions of a political nature.

In particular, in 2017 the President of the United States Donald Trump decided to bring the troops back to Afghanistan, to increase a presence in the territory that had lasted since 2001. To convince the President to approve a continuous warfare in Afghanistan, the then National Security General Herbert McMaster decides to show him Brun’s photograph. The sight of free and smiling women acts as an engine for the return of the troops, with the objective to continue the mission of modernization of Afghanistan. Clearly, it would be simplistic to think that a photograph was the sole cause of this decision. But the reality is that it played a crucial role, speaking to the guts of a Western President.

Reality turned into fake representation

Ultimately, what interests us is to emphasize the influence of emotions in the decision making process and the misperception of reality that is still being fueled in the media. The picture is real, it is not a photomontage. But what it shows us is a limited reality, which ends up becoming the only known perspective. This happens because the subjects of the image cannot speak for themselves and therefore truthfulness is left to imagination and decontextualisation.

In fact, in this story, we can trace the typical elements of any fake news: the use of photography for political purposes, specifically the return of US troops to Afghan territory. The indignation provoked in the media by the photograph, whose diffusion followed the same parameters of a made-up fake news: it was spread quickly, in moments of strong political crisis. The result is that its presence was so strong in the media that it did not allow a real process of questioning. Users did not really want to investigate the socio-political context of the time, the fragility of the reforms in favor of women’s rights and their scope of intervention relating solely to the urban context of Kabul.

The picture was just taken as a genuine portrait of a society that once was modern. The image hits the stomach and the nostalgic element triggers indignation. Therefore, it is manipulated with comments as many times as it is shared, making it unnecessary to investigate, with the presumption of having all the elements to be able to judge: it is fresh meat for clickbait and the usefulness of double checking is not perceived by users.

In an article written by Ajam Media Collective on the topic, we read: “Instead of defining women’s freedom in terms of social, political, and economic rights – like literacy, access to healthcare, and so on – both positions reduce “freedom” to how much skin is showing or not showing. A photograph becomes all it takes to decide that women are free or not free. This narrative, however, is not only misleading – it is also extremely dangerous, as shown most clearly by its use to convince Trump of the justness of endless warfare. This narrative suggests that the despair that continues to overwhelm Afghan society is rooted not in the widespread corruption, lack of economic opportunity, obliteration of large swathes of the built and natural environment […] but instead in the lack of miniskirts that fail to grace Kabul’s streets.”

In her book “Regarding the Pain of Others”, Susan Sontag states that pictures never speak for themselves. Their representation and the meanings attached to them change according to whom they are shown to. And how they circulate. Photographs can be misread as evidence, cutting out the complexity of context. In the end, a news is trustworthy when its content is contextualised. It does not solely rely on straight forward solutions that trigger emotional responses. Without that, an image is just an image or a piece of art. And its interpretation can be a powerful tool to allow important and potentially dangerous decisions.

Carlotta Sofia Grassi